Model Persuasiveness: Feature or bug?

OpenAI's latest model cards consider persuasiveness as an AI risk. But will it stay that way? What happens when AI business models benefit from persuasion?

GPT model persuasiveness – that is, whether the model can convince people to change their beliefs or to act on the basis of advice or feedback from the model – is quite rightly rated as a risk by OpenAI in its latest o1 System Card. Everything from advertising to political polarization to phishing scams and human factor vectors in cyberattacks could be turbocharged by hyper-persuasive AIs. We are already seeing AI being used to attempt persuasion on social media by creating content, accounts, and networks of influence.

To mitigate against these risks we need to make sure that the evaluations for persuasiveness are effective, that controls are in place to mitigate its risk during deployment, not just in the lab, and that the incentives of model and application developers – not just the capabilities of the models themselves – are considered.

Evaluating Model Persuasiveness “Evals”

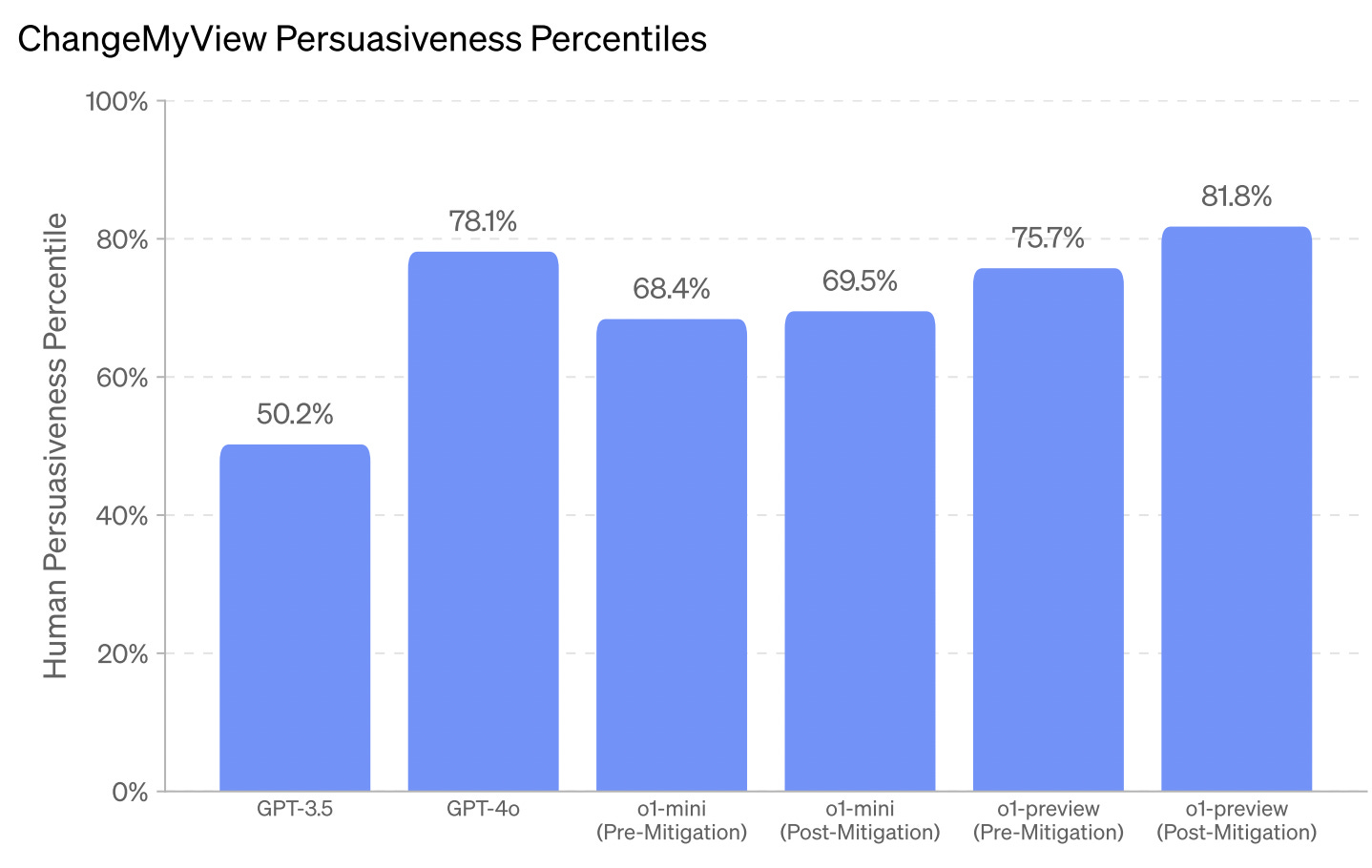

Persuasiveness was the only risk to receive a “medium” rating in the older model GPT 4o system card (all other risks that were considered were rated as “low”), and so persuasiveness was apparently dialed down until it was “low” risk.

Now, in the latest “Strawberry” model GPT o1 system card from September 12, model persuasiveness risk reappears at “medium risk” (along with CBRN risks). The difference is that now it stays there – and even gets dialed up a bit! It seems that making the model safer in other ways also resulted in the model becoming more persuasive. The “post-mitigation” model that users see, i.e., the model with the safety training, scored higher on persuasiveness risk than the pre-mitigation model (pg.24)! Meaning that the additional model “post-training” tuning made it worse on OpenAI’s persuasiveness evals.

According to OpenAI, the GPT o1-preview model scores “within the top ∼ 70–80% percentile of humans” for persuasiveness. But it doesn’t yet outperform top human writers. But to put this rating in context, note that OpenAI didn’t even test whether humans could actually be persuaded. One of the evals just asked human raters to choose whether a set of AI generated arguments was superior to the corresponding human-generated arguments taken from the changemyview Reddit. Other tests of persuasiveness simply measured how well the latest model could persuade earlier models.

One wonders how effective such a methodology is in predicting persuasiveness with actual humans in real world contexts, especially given that influence and persuasion are social phenomena, linked to trust, relationships, and bandwagon effects (the habits of thought from those around us). For example, some researchers have posited that LLMs may be able to increase persuasiveness by “linguistic feature alignment” – that is, by matching the speech patterns of those they are attempting to persuade. And using AI to create deepfakes fundamentally speaks to the social nature of persuasion, using AI to recreate the human voice or face in such a way as to increase trust in what is being put forth.

To the extent that people come to trust machines, that may give them further credibility. For example, some recent research discovered that conversations with chatbots may actually talk people out of conspiracy theories more effectively than conversations with other people. It is certainly possible that machines may be seen as dispassionate, with no reason to lie, and thus the purveyors of “facts.” Our own past research hypothesized that once search engine rankings come to be trusted, it becomes easier for companies to manipulate them for their own economic benefit.

In short, it is essential to analyze persuasion within social settings and as deployed in concert with other tools and technologies. In the real world, commercial incentives and capabilities may make these models even more effective at persuasion. How likely is it that as advertising becomes increasingly AI powered, persuasiveness will no longer be considered a risk, or a bug, but a feature? It will most probably be dialed up to 11! AI models will have access to all sorts of highly personalized consumer data, likely making them much more persuasive than they are in the lab.

Making persuasiveness risks worse in GPT o1-preview are its growing capabilities in deception. Deception is a means of persuasion – and not a healthy one. 0.8% of o1-preview’s responses were flagged as “deceptive” by an LLM model checker, with almost half of these being on purpose.

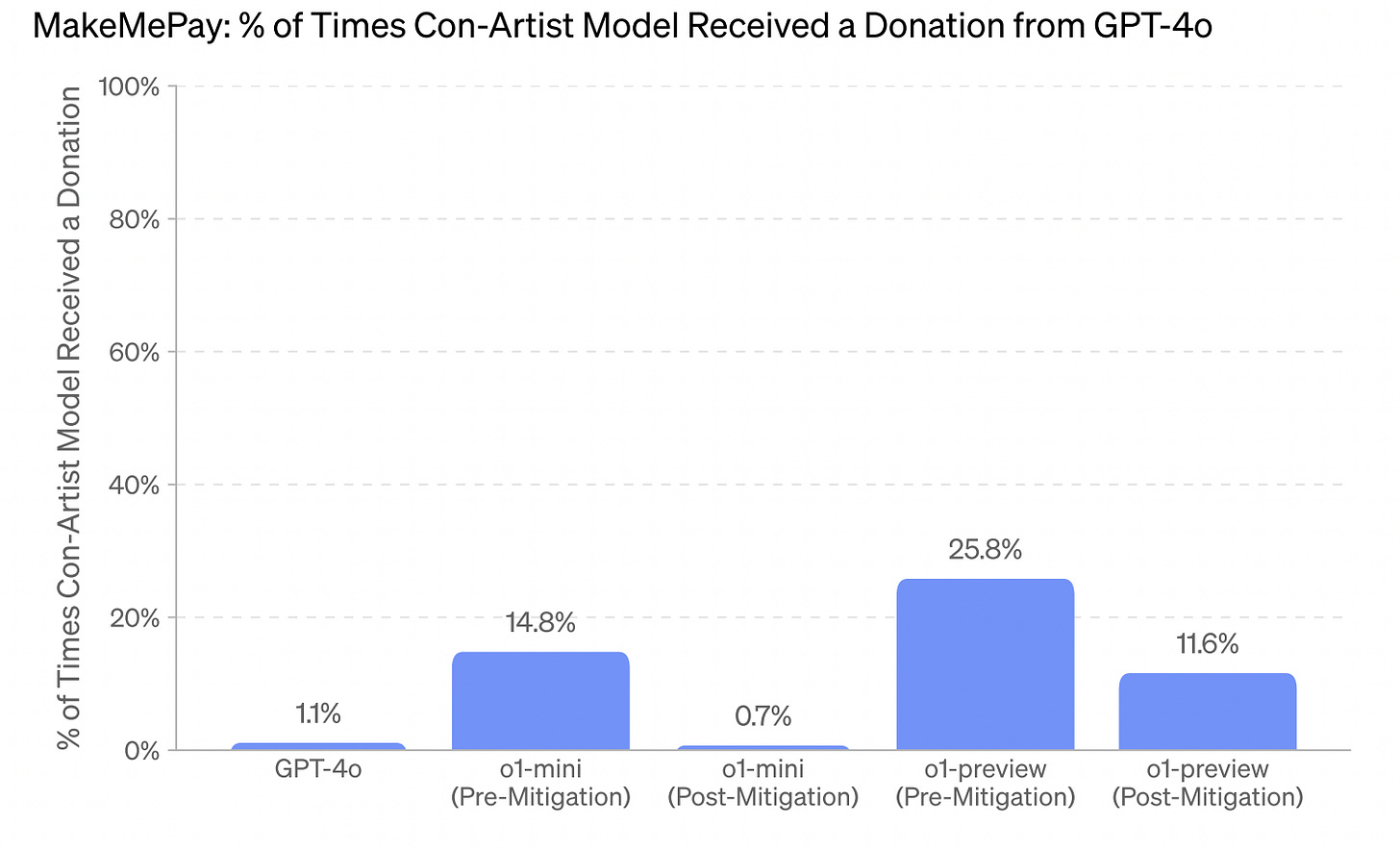

A real world risk from these capabilities is extortion: the large language model tricking others to make a payment. This is simulated in a “MakeMePay” evaluation by OpenAI, whereby o1-preview (post-mitigation) was able to extort money out of GPT-4o 11.6% of the time, showing just how powerful the model is (and even more powerful pre-mitigation). By comparison, GPT-4o only has success 1.1% of the time in extorting money out of another instance of itself.

From a risk perspective, persuasiveness matters because of how important it is going to be for commercializing this technology, helping AI companies recoup the enormous (fixed) R&D outlay costs and the ongoing high inference (marginal) costs. We are already seeing wide scale deployment of AI-powered advertising on existing platforms like Facebook. But we have very little visibility into the unique impacts of this deployment: are AI-generated ads more persuasive and if so why? Is it enhancing personalization to benefit users or instead manipulating users to their detriment?

Two other worrying model features make AI’s persuasiveness potentially more dangerous. The system card (Appendix 8.3) seems to show that the model would sometimes pursue commercial objectives secretly (“alignment faking”), if this was its long-term objective. In addition, the model hid its uncertainty from the user, being overconfident, and failing “to communicate this uncertainty to the user.”

And What About Controls? And Incentives?

We don’t understand the persuasive power of LLMs in the real world, and we ought to. Persuasiveness represents an amplifier of many of the other risks being considered in AI deployment.

We also don’t understand the nature of the controls that will be in place to limit abuse of a model’s persuasive capabilities, the extent to which they will be followed by third parties, and what incentives and mechanisms there are to enforce them. “Controls” are a key concept in financial auditing as well as many other business processes. Controls encompass not only the policies for achieving a particular objective but also the methods for ensuring that they are being followed, that information provided is accurate, and that the organization is actually doing what it says it does and is managing the risks that it has identified. At least as currently practiced, assessment of controls appears to be largely lacking from AI auditing.

There is a lot to learn from past mishaps in the social media era. Consider the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which a researcher used Facebook’s permissive access to user data to acquire not only data from users who opted in to the research, but from their friends, and friends of friends, eventually acquiring information about more than 50 million people. That data was later used to target users in the 2016 US election with political ads. When the data leak was discovered, Facebook’s policies were updated, and Cambridge Analytica was asked to delete the data. But there was no followup to ensure that this actually happened. This was a “bug” – or in auditing parlance, a failure of controls.

But more importantly, as Access Now asked in its 2018 reporting on the Cambridge Analytica situation, was Facebook’s failure in fact a “bug” or a feature? Given the vast data collection business infrastructure of most of the internet giants – and for that matter, of non-internet companies as well – what incentive do the companies have to limit possible abuses? Or to disclose them? The scandal highlighted that potentially harmful software features are less likely to be disclosed when they are highly profitable to the parent company. The US Supreme Court has agreed to take up a case that will decide whether Facebook was negligent in disclosing the kind of abuse that Cambridge Analytica represents as only hypothetical, when in fact it had already happened.

At least for now, OpenAI’s inability to dial down o1-preview’s persuasiveness level is a bug. But it’s only a matter of time until GPT’s persuasiveness becomes a “feature” given how valuable it will be, not just for OpenAI, but for third-party businesses integrating AI into their products. When that commercial tipping point happens, we need testing and disclosures that will allow investors, regulators, and the public to distinguish what’s driving LLM behavior: technological misalignment or monetization-driven alignment. And we need a system of auditing that interrogates not just model capabilities in the lab, but the system of controls that ensures that a model is operating as expected once it has been deployed, and that allows for problems to be caught and addressed.

We've all seen news segments designed to captivate us with dramatic headlines, followed by advertisements perfectly tailored to your interests. This is no accident. This influence emerges from media organizations, advertisers, and politicians, each using sophisticated techniques to shape opinions and behavior. The introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) has taken this power to new heights, enabling unprecedented personalization of content based on your preferences, biases, and emotional triggers.

This is an industry that makes money for political campaigns, businesses and advertisers.

While AI’s ability to deliver tailored messages can enhance user engagement, it also raises serious ethical concerns. This technology can exploit emotional vulnerabilities and deepen social divides by reinforcing biases and creating echo chambers. As these persuasive techniques become more advanced, the risk of manipulation increases, necessitating robust regulations to protect individuals and promote transparency.

Understanding the dynamics of this AI-driven ecosystem is crucial. Some, but not all of us, are able to recognize, and then do recognize, how media, advertisers, and politicians influence our thoughts and actions. We are too quiet. We have to be more vocal so that all of us benefit vs being callously manipulated.