What Auto Safety Teaches Us About AI Safety

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked.” - John Gall, Systemantics

In 1923, there were 21.65 deaths per hundred million automobile miles traveled in the United States. In 1966, there were about 5.5. Today, about 1.1. How did this happen? And what can it teach us about AI safety?

Think back to some of the earliest safety features for cars, things we now take for granted. Electric headlamps for autos were invented in 1898, and gradually became widely available, but they were not required on automobiles till the 1940s. So too, windshield wipers were invented in 1903 but not standard equipment on cars until the 1940s.

In 1965, Ralph Nader’s book Unsafe at Any Speed documented the resistance of auto manufacturers to the added cost of auto safety and created a public outcry. In response, the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) was created in 1966, and starting in 1968, manufacturers were required to install seat belts in the front seats (although it was not made mandatory to wear them until the 1980s.)

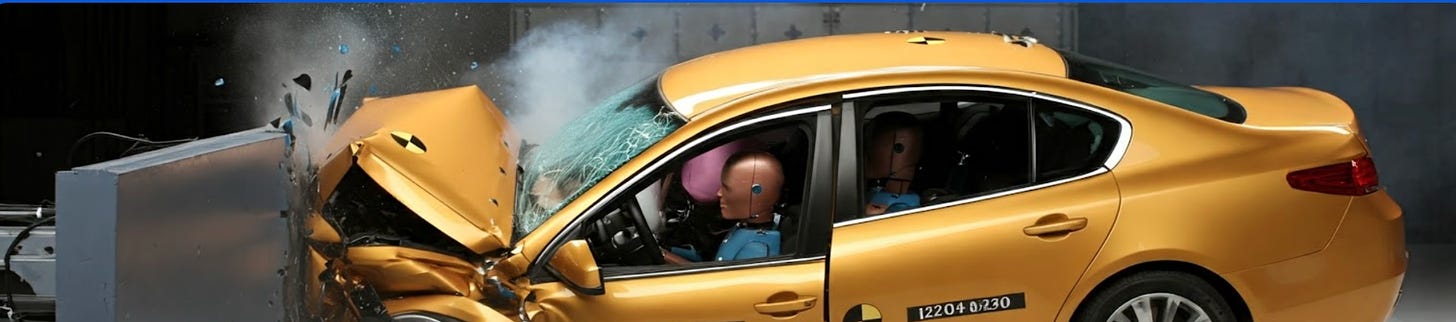

The market too began to respond. In 1972, Volvo introduced a concept car focused on safety, introducing many of the safety innovations such as airbags and crumple zones that we take for granted today. The National Highway Transportation Safety Agency began to test how long it takes a car to brake at different speeds, what happens to it when it crashes, and the effectiveness of methods to limit the harm of a crash. Auto manufacturers are not required to submit their vehicles for testing, but the NHTSA releases safety ratings for all new cars based on its tests. Publications such as Consumer Reports and Car and Driver took these ratings into account when ranking the appeal of new and used cars, creating incentives for manufacturers to invest in safety. The NHTSA also has the ability to issue safety recalls when a widespread problem has been discovered that affects many vehicles.

But that was far from the beginning of the story. What led to all the declines between 1923 and 1965?

An automobile doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is operated by a driver, sharing the road with vehicles operated by other drivers, pedestrians, bicycles – and in the early days, and even today in many parts of the world, by animals and vehicles drawn by animals. Safety is as much a product of the infrastructure over which cars operate – as seen by recent efforts to introduce protected bike lanes – by driver training, and by norms and laws about safe vehicle operation – as it is by the safety characteristics of the vehicle itself.

There’s an interesting co-evolutionary lesson here. As the quality of the roads was improved, they became safer, but that also made it possible to go even faster. And as autos went faster and became more ubiquitous, they needed to evolve to become still safer. That process continues today. All manufacturers compete to add safety features, innovations such as active braking, collision and lane departure warnings, backup cameras, and increasingly, cameras and other sensors for monitoring drivers for sleepiness, inebriation, or inattention.

The first speed limit was introduced in 1901, and the speedometer was invented in 1902 and became standard on most autos by 1910. One of the most interesting lessons from the regulation of speed limits, though, might be the evolution of the disclosures about them, in the form of road signs. The size and placement of signage was formalized in 1935 with the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (link is to the current version at the US Department of Transportation.) That first edition also specified for the first time that speed limit signs had to be posted whenever the speed limit changed. In 1948, yellow advisory signs were added to identify a separate speed limit based on risk, such as on a sharp curve. Put that together with a speedometer that gives feedback to the driver and you have the basis for fairly effective self regulation, plus a basis for enforcement.

Road markings displayed a similar evolutionary pattern. In 1911, Wayne County, MI was the first to introduce a center line down the middle of the road. Eventually a “language” of center lines was developed to signal safe turning and passing behavior, and side lines were added to mark the edge of the road. The lines were made more permanent and more easily visible at night. The first traffic light had been introduced in England in 1868, but it wasn’t until the 1920s that they became common, and the modern convention of red, yellow and green lights was adopted. Road markings and traffic signals were standardized in Europe in 1931 and in the US in 1935.

Speed limits are set by states and local jurisdictions, not the federal government, and vary by the type of road and sometimes by the type of vehicle: one limit on interstate highways, another on state highways, yet another on county and city roads, even by type of neighborhood (business or residential), near a school or not, one limit for passenger automobiles and another for trucks and buses, and so on. Despite the statutory variation, most states are guided by the Uniform Vehicle Code and Model Ordinance, a document developed starting in 1959 by a now defunct nonprofit organization of representatives from state governments called the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Laws and Ordinances (NCUTLO). The UVC is very data-driven, for example, advising states that they “establish speed zones upon the basis of an engineering and traffic investigation,” and asserting that “It is not based on theory; it is based on actual experience under various state laws throughout the nation.”

Then there’s the matter of license plates, an innovation designed to link automobiles with their owners and to make them easier to track. In 1901, New York was the first state to require automobiles to be registered and linked to their owners, followed quickly by California. In 1903, Massachusetts took the further step of actually manufacturing and issuing an official license plate. By 1918, all 48 states required license plates, but their size, format, and placement wasn’t standardized until the 1950s. And starting in 1954 each car was required to have a unique Vehicle Identification Number affixed permanently to the vehicle itself, as a way to ensure that license plates weren’t swapped to other vehicles, thus obscuring their ownership. The VIN is a rich, meaningful identifier, encoding the country of origin, the maker of the vehicle, various features of the vehicle such as body style and type of brakes, the model year, the assembly plant, and where it fits into the output of that plant. Oh, and there’s even a checksum digit.

Drivers themselves were also required to get licenses fairly early on. New York was again the leader, requiring a driver’s license starting in 1903. The first age restrictions were introduced in Pennsylvania in 1909, and use of a test to establish the driver’s ability to drive in Rhode Island in 1908. The first driver’s education curriculum was developed in the 1930s. But drivers’ licenses were not required by every state until North Dakota finally did so in 1954.

Private insurance became a kind of parallel commercial regulatory system, with risky vehicles and risky behavior leading to higher costs. The first automobile policy was sold in 1897 in Massachusetts, at the request of a customer. But by 1925, Massachusetts had made auto insurance compulsory. Other states followed, though even today, neither Mississippi, New Hampshire, nor Virginia require it. Insurance provides a kind of fine-grained regulation, with premiums taking into account factors such as location, age, the cost of the car, the driving history of the individual, and even, in the age of GPS, considering factors such as miles driven and observance of speed limits.

Advocacy groups and the evolution of public norms (and the technology to enforce them) have also continued to drive safety. Standardized tests for sobriety had been developed in the late 1970s, but it wasn’t until 1984 that the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, inspired by activism from organizations like Mothers Against Drunk Driving, introduced a maximum blood alcohol content (BAC) limit of 0.08% for all drivers, established a national legal drinking age of 21, and mandated license suspensions for repeat offenders. Interestingly, the age limit was not mandated by the law – drinking age was regulated by the states – but the national law incentivized states to raise their drinking age by withholding a percentage of federal highway funds unless they did so.

Despite these improvements, a third of automobile accidents in the US still involve speeding, and 32% feature drunk drivers. The latest innovation in safety involves yet another intersection of technology and regulation. Advanced drunk and impaired driving technology can use sensors to analyze the driver’s breath, or even to detect ambient alcohol levels inside the vehicle. The societal and regulatory decision at the coal face of emerging regulation is whether to mandate such sensors along with an ignition interlock that, if levels are high enough, may prevent the vehicle from operating. If the past is any guide, this decision is likely to be made on a jurisdiction by jurisdiction basis.

Lessons for AI Safety

From even this brief and superficial history, you can see a number of possible lessons for AI safety:

Auto safety is systemic, not just limited to the safety of the vehicle itself. It includes consistent rules of the road, reflected in the infrastructure of those roads (road markings, traffic lights, and so on), training and licensing to ensure that the rules are understood, and mechanisms for their enforcement. By contrast, AI safety is currently focused mostly on the model (much as if NHTSA crash testing were the only way we dealt with automobile risk) and the ability of bad actors to get around model safeguards. Note that one safe car design doesn’t make the roads safe if other cars, other drivers, or the roads are unsafe. In fact, while large vehicles are safer for their drivers, they are less safe for others driving smaller cars.

Automobiles and other vehicles are registered and uniquely identified. This aids in tracking bad behavior and links vehicles to their owners. Because many of the major AI models are centralized, there is a possible mechanism for tracking, but it doesn’t extend to open source models, other custom models, or AI applications. Gillian Hadfield’s proposals for an AI registration requirement are an intriguing first step. Registration is particularly important when we look towards a future of independent AI agents.

Drivers are also licensed. User behavior, especially with regard to identified risks (such as speeding or driving under the influence), is measured and regulated, not just the capabilities of the machines they operate. Interestingly, at least for the large centralized models, AI users are subject to a kind of private licensing via the requirement for at least a login account and potentially a subscription. But again, open source and private models do not have even this licensing requirement.

There are “rules of the road” that guide driver behavior. There are similar rules for the use of AI. For example, Anthropic publishes an extensive list of forbidden behaviors in its Usage Guidelines, such as not exploiting minors, damaging critical infrastructure, inciting violence, compromising privacy, generating psychologically damaging content, misinformation, fraud, or sexually explicit content. But despite the long list of prohibitions, there is no indication of how the company polices such behavior or what the consequences might be. Anthropic notes that your conversations may be flagged for trust and safety review, but how will the user even know that they are potentially infringing?

A policy document on a website that few people read is insufficient. In the automobile realm, road signs, lane markers, traffic lights, guardrails, and the vehicle speedometer provide a kind of visual language by which rules and best practices are disclosed to drivers. They can change driver behavior and help to set driver norms. For example, automated speed display monitors have a measurable calming effect. It isn’t clear what the AI equivalents may be, but we should be alert to their emergence in practice, much as drivers, communities, and states came to respond to the challenges of faster and increasingly numerous vehicles. Real time feedback by AIs when their guardrails are being tested is certainly one mechanism, but it may be insufficient if there are no consequences for repeated attempts to get around them. This is a major contrast with auto safety, where…

There are mechanisms for enforcement. Driving too fast, or under the influence of alcohol, or in other ways that are dangerous, can lead to fines or even arrest and suspension of the right to drive. Police officers don’t just rely on their judgment, but are aided by technology such as radar guns and cameras in determining violations.

Enforcement is tightly linked to the infrastructure. That is, it is done on the roads, where the cars operate, not at the factory where they are made. Again, for the large, centralized models there is the possibility of private detection of bad behavior and enforcement of rules, but private and open source models operate outside this possible set of constraints. One possibility is to think about methods of enforcement at the cloud infrastructure layer. In either case, though, it is unclear how the providers of these models or cloud infrastructure will enforce their rules.

Rules were not made up all at once, but evolved over time out of best practices that were eventually standardized. States often led the way in developing these standards. This goes against the EU's approach of being comprehensive up-front, and could be a way that U.S. AI regulation differentiates itself. State level AI safety bills are being introduced every day. Rather than being comprehensive, they should try to solve individual, clearly defined problems, one at a time. This will allow best practices to evolve, rather than being cast in stone when we don’t really understand what works.

Regulation is not just done by government, but also by private actors. Insurance companies, auto ratings publishers, and activists form a kind of “regulatory market” that complements and builds on the underlying architecture of government regulations. A market like this is enabled by a system of clear, enforceable rules that are understood by all parties.

This is the first draft of the intro to a larger report about lessons from the evolution of auto safety regulation. We intend to create such reports on a variety of regulatory regimes.