Quality over Quantity

Why it’s not necessarily a bad thing that Trump wants to reduce corporate disclosure frequency – and how to combine it with meaningful disclosure on AI

From Frequency to Depth

The Trump administration’s push to move away from quarterly corporate reporting has sparked a debate about the value of corporate reports, with important takeaways for AI-related reporting requirements.

John Authers noted in his recent column, quoting Sarah Williamson at FCLT Global, that disclosures are not really about timing, but “materiality” (i.e., importance): “What really matters…is the materiality of what to tell investors, not the periodicity.” And the bar for what is material should be lower, she argues. That is, more things should be considered important for companies to disclose rather than fewer.

This principle has potentially far-reaching implications for AI disclosures. Rather than getting caught up in debates over how often AI companies should report, we should be asking: What risk events in AI systems are already material enough to warrant immediate disclosure by corporations? And how exactly should these be disclosed by public companies?

In line with our previous work, we call for prioritizing disclosure depth over disclosure frequency – it's about quality over quantity.

Drawing on the SEC’s 2023 rule on cybersecurity incident reporting, we propose a dedicated AI risk item in the 8-K Form — an event-driven, impact-based trigger whenever an AI incident materially affects the company. We also propose adding a standing item to the annual 10-K corporate disclosure Form on AI that explains a company’s risk management, strategy, governance, and key dependencies. In the interim, the SEC should issue Disclosure Guidance with concrete examples of AI events that may meet materiality thresholds and how they map to existing 8-K and 10-K items.

In doing so, we can advance AI-related disclosures that are more comparable, timely, and granular — and that materially strengthen company risk mitigation. And as a bonus, standardizing these disclosures (ideally with machine-readable tags) will also improve decision-usefulness for investors and oversight by regulators.

Cyber Risks as a Model Disclosure Framework for AI-Related Risks?

Perhaps as a result of a recent proposal from the Long Term Stock Exchange (Disclosure: Tim O’Reilly is an investor), which was reported on by The Wall Street Journal on September 8, President Trump recently proposed that public companies’ quarterly reporting should instead become bi-annual (twice a year). Trump certainly made the case for it based on the same LTSE argument: that quarterly reporting places undue burdens on public companies and pushes executives into short-termism – so-called “expectations management.”

Time-based reporting requirements incentivize companies to structure decisions around a company’s financial calendar, which might delay crucial information being released to the public as it occurs.

Enter the 8-K Form. The 8-K is sort of like a breaking news bulletin, since through it significant events are announced by the company within four business days. But the list of “Items” varies in what triggers them. Many items are triggered automatically by an event, like a corporate bankruptcy. Other items on the list are based on the company’s judgment around whether the event is “material”1 i.e., sufficiently likely that a reasonable investor would care about it – and only then would they file an 8-K form. A cybersecurity incident is one such “if it’s important enough” thing to disclose (Item 1.05).

An important and relatively new corporate disclosure requirement that uses the 8-K Form is the SEC’s 2023 Cybersecurity Incident rule for public companies. It says that when a company suffers a material cybersecurity incident it must report it to shareholders within four business days through the 8-K Form. And when it’s a material cyber event impacting shareholders, then it can be filed through the newly added Item 1.05, specifically for cyber incidents.

In combination with strong SEC enforcement, the rule seems to have worked. Cyber incidents are disclosed in a far more timely and comparable manner now, and companies appear to be devoting more resources to the problem. Moreover, companies absorbed these new requirements with ease because they were well prepared from previous guidance.

Part of the Rule’s innovation is that the material event-triggered 8-K filing for cyber incidents sits alongside a standing annual 10-K disclosure requirement for companies specifically for cyber-related issues (Reg S-K Item 106), covering things like board and management oversight, processes for identifying and managing material cyber risks, whether such risks materially affect the company, and more.

The question then is whether AI-specific risks require a similar treatment to cyber ones. Below we show that a substantial “disclosure gap” already exists for AI, which only enhanced AI-related disclosures can fill. This is the gap between the AI-risks already out there facing AI companies, and what they are currently disclosing.

Evidence on the Disclosure Gap

That AI-specific risks are impacting corporations is now very apparent. Fisher Phillips’ AI litigation tracker for the U.S. currently shows 92 cases.2 Litigation on securities class action lawsuits covering false or misleading statements on AI is on a near exponential rise in the U.S., from 7 cases in 2023, 14 cases in 2024, and 12 cases so far in 2025. In Garcia v. Character.AI & Google, the court has let the case proceed (May 22, 2025) over a teen’s suicide, allegedly encouraged by a chatbot’s messages. Claims include wrongful death, negligence, and deceptive trade practices. The point being that AI-usage now exposes companies to a range of risks from product liability & negligence, wrongful death, defamation, and publicity and privacy, to name but a few.

To manage growing AI-specific risks, companies are trying to disclose more to their shareholders, even if only superficially. An analysis by Arize AI, as reported by the Financial Times, found that 56% of Fortune 500 companies cited AI as a “risk factor” in their most recent 2024 annual 10-K reports.3 Netflix, Motorola, and Salesforce all discuss AI-specific risks.

Even though AI-risks in the 10-K are no longer a niche, they are also not yet particularly useful. SEC staff letters to companies show that much of the guidance was thin on details. Staff consistently requested more specifics.

Aware of the AI-disclosures gap, the SEC launched in 2024 AI-specific guidance covering AI washing, conflicts of interest, and systemic risk, along with enforcement actions.4 The SEC now even has a newly dedicated Chief AI Officer (CAIO) Valerie A. Szczepanik, who will oversee a new SEC AI Task Force, though its focus is more on internal innovations.

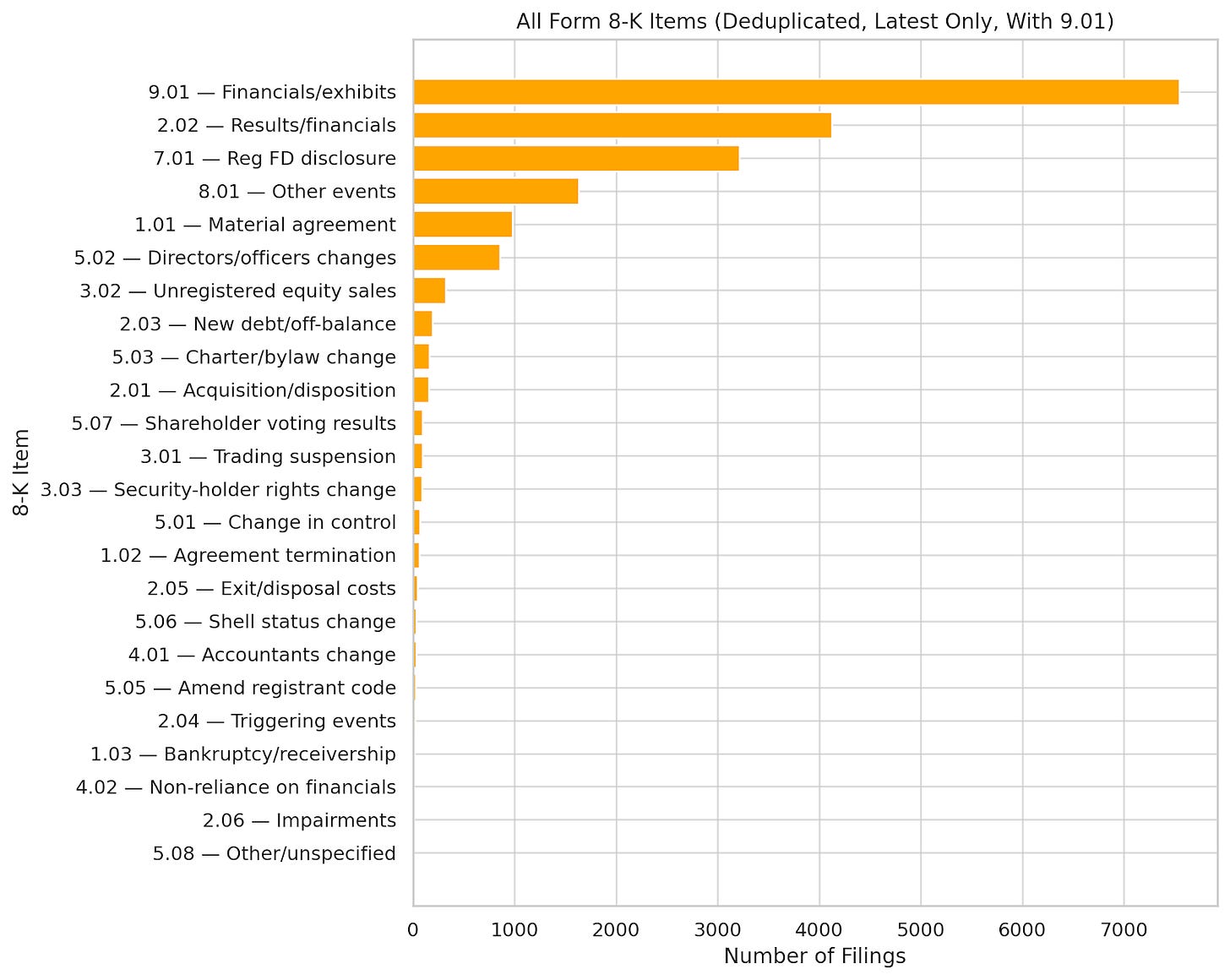

Finally, with respect to the 8-K, we constructed our own dataset of all AI-related event-driven filings since November 1, 2022, covering 1,741 corporate issuers. It highlights at least three key AI-related corporate disclosure gaps:

No Risks Here. The first is that 8-K disclosures almost exclusively concern a company’s commercial ventures (Figure 1 below): covering important agreements (Item 1.01) – such as model licensing, cloud/compute commitments, strategic data deals, and reseller/partnership agreements; but also Financial matters (Item 2.02). Safety and guardrails, i.e., AI-risks, rarely feature (though we have not yet done a full textual analysis).

Figure 1. 8-K filings by public companies in the U.S. on artificial intelligence and generative AI, by Item topic.

Confusion reigns. Secondly, most disclosures for AI-related impacts are through Item 8.01: a voluntary catch-all event category useful for AI updates that are not yet a mandated material trigger but still market-relevant. This means that companies are not yet sure where to put such AI-triggered events and/or are unsure when an event is sufficiently material to disclose it elsewhere.

Big firms need a 10-K mandate. Finally, 8-K filings on AI-related matters are driven by smaller companies. Big Tech’s 8-K disclosures are not very prominent: AMZN (14), NVDA (11), MSFT (10), META (12), GOOGL/GOOG (9 each) amount to well under 1% of the total filings we examine.

Practically, this means that any new 10-K requirement to cover AI-specific business activities and risks in detail could significantly enhance market transparency, since these mega-cap firms have an outsized impact on the AI market already (together with OpenAI, Anthropic, and a few others).

So What Should We Be Aiming For?

1. Guidance Note. To get the ball rolling, an SEC guidance note (called “CF Disclosure Guidance”) could help companies understand how existing disclosure rules apply to AI. It’s not binding law, but it can strongly influence company filings and SEC actions. For example, the 2011 Cybersecurity memo (Topic No. 2) told issuers what to discuss under Risk Factors, MD&A, Business, and other items in their 10-K report. For AI, it could provide similar guidance, giving practical and specific examples of things to discuss under relevant Items, avoiding boilerplate discussions, covering their business (S-K Item 101), risk factors (S-K Item 105), trends and uncertainties (S-K Item 303), and more.

For 8-K material events triggered by AI requiring urgent filing, SEC Guidance might discuss potential quantitative and qualitative triggers to monitor for potential 8-K events that require further internal company discussion. For example:

A major quantitative change (relative to a historical baseline) in important KPIs, possibly driven by AI changes to DAU/MAU, time-on-platform, ad CTR, conversion rates, credit-approval rates, charge-offs, loss ratios, etc., might require further company review. As could a notable increase in harmful model outputs, jailbreak success rates, self-harm exposure, fraud detection, or similar operational risk metrics monitored that are far outside of normal behavior.

These metrics are already monitored internally and so can easily be used to trigger a potential 8-K filing.

Qualitative triggers could similarly be used to trigger a corporate 8-K disclosure review and might include things like: AI objective and optimization changes, guardrail and policy changes that are likely to alter harmful output rates or regulatory exposure, and data provenance or infrastructure shifts — including new sensitive datasets, migration of core features to third-party models and APIs, and significant compute capacity losses.

2. Create a new AI-risk item on the 8-K disclosure Form for significant events as they happen. Companies already use the 8-K Form to alert investors when something important happens between annual or quarterly reports. The idea here is to add a dedicated item for AI-related incidents, so that there is a clear place to report them when they matter. This can help ensure that companies do not skip reporting the “risks” when disclosing material AI-related events.

“Incident” should be understood broadly: for example, a model failure that misprices loans, an AI system outage that interrupts service, an AI-driven error that requires customer remediation, or a sudden loss of access to a third-party model that a product depends on.

The key point here is that this sort of corporate disclosure is impact-based rather than technology-based. In other words, the trigger is not “an AI model changed,” but that “the change or failure had a meaningful effect on operations, customers, compliance, or financial results.” This mirrors how materiality works across corporate reporting: if a reasonable investor would want to know about it because it changes the picture of the business, it belongs in an 8-K.

3. Add a standing AI section in the annual 10-K Form that explains how a company manages AI. One-off 8-K event reports are, by themselves, insufficient. Investors also need a clear, yearly picture of how a company runs its AI-related activities, covering: how it is used in products and operations, who oversees it, what the main risks are, and what controls are in place. A new 10-K item would provide that exact structure, thereby encouraging companies themselves to adopt a longer view of these risks.

Companies would explain their approach to risk management (how they test and monitor systems, how they roll out changes, how they respond when something goes wrong); their strategy (where AI fits in the business and why); and their governance (who is accountable at the management and board level). They would also describe key dependencies that could affect reliability or cost (such as reliance on outside model providers, critical data sources, or a single cloud vendor), along with any concentration risks that come with those choices.

The goal is not to jam in unnecessary detail into the 10-K but to make the business implications of AI understandable to the investing public: where the leverage points are, how failure is prevented, and what the plan is when problems occur.

Finally, labeling the main AI elements with standard, machine-readable (iXBRL) tags (the same way the SEC does for several other disclosures, such as the SEC’s cyber rule) would let analysts and watchdogs compare companies more easily and spot patterns over time.

Empower Markets with Information

As AI systems become more powerful and more integrated into critical infrastructure, pressure for more prescriptive regulation will grow. By establishing simple, effective disclosure regimes now, backed by appropriate institutional capability at the SEC, we can create the foundation for more sophisticated governance that becomes integrated into third-party regulatory markets as the technology matures. Information empowers markets.

The question is not whether we need AI disclosures from corporations, it’s whether we will get them right. For us that means focusing on enhancing the quality of corporate disclosures rather than the quantity.

“Material” is defined by the courts to mean whether there is a substantial likelihood a reasonable investor would view it as important ( TSC v. Northway), and weighs the probability of an event happening against its magnitude (Basic v. Levinson) – something the AI risk community also buys into.

Alston & Bird’s 2024 study found that 46% of Fortune 100 companies included AI-related risk disclosures in their annual 10-K forms. Disclosures fell broadly into five buckets: (1) cybersecurity risk; (2) regulatory risk; (3) ethical and reputational risk; (4) operational risk; and (5) competition risk.

Diennial reporting certainly favors companies over investors. When companies have listings in the UK (diennial reporting) and the US (quarterly reporting) there was a lot of interest in getting the quarterly report for UK investors.

It would be nice if the quality of the reporting improved, but would it? There is a lot more than being concerned about AI risks.